An 80-year-old Letter

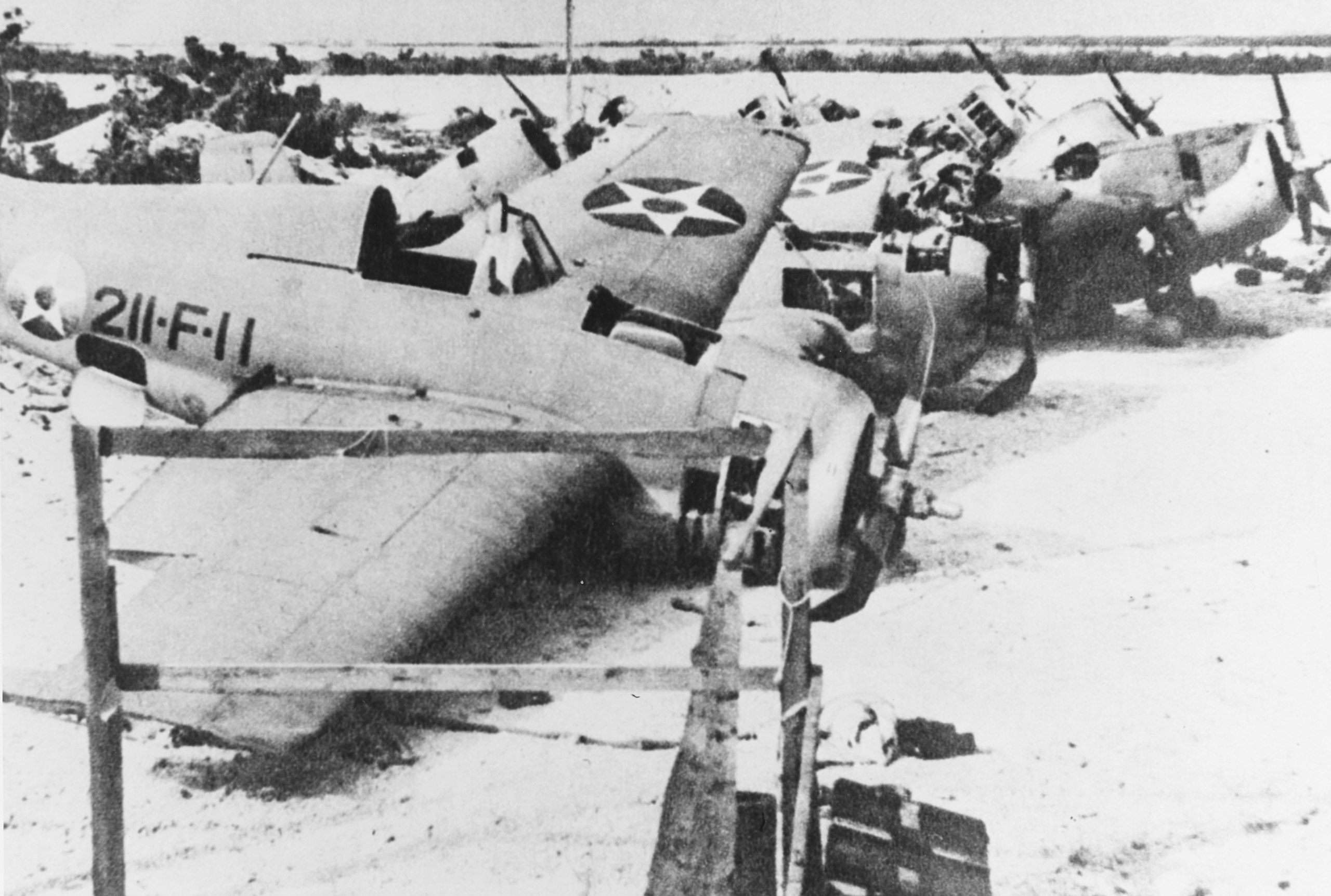

[A repost from the 75th anniversary. Yes, the pics are graphic. Look at them. Own them. Be glad they’re in black and white.]

As the 80th anniversary of the launch of Overlord arrives, it’s important to remember that it was just part of a very big picture, the beginning of the end of World War II. Up until that point, it had been a very long, very hard slog. But afterwards you could practically see directly from the beaches of Utah, Omaha, Sword, Juno and Gold on 6-Jun-1944 to the deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on 2-Sep-1945. The war now had its expiration date.

No one cheered harder for the faint glimpse of the end than P.o.W.s in Japan, Korea and China. A few of those had survived four years of torture, starvation, beatings, illnesses such as beri-beri and even being bombarded by their own Army Air Force; they were the survivors of Wake Island, which resisted overwhelming Japanese invasion forces between 8-Dec and 23-Dec-1941. Had it not been for Overlord and Manhattan, those men would have died. Instead, they beat the odds thanks to Truman and Ike, Normandy and Trinity. (To quote directly: “Thank God for Harry Truman and thank God for the atom bomb!”)

I always think back to 1989, when as a newspaper reporter, I was privileged to meet just 11 of the Wake Island survivors, who gathered fairly often for small-scale reunions. That year, while working as a reporter who occasionally wrote some features about WWII vets, I got a call from a friend of mine, Marie Smith, (who had kept me sane during my cursed four months while we worked at <shudder> Wal-Mart), to tell me about an upcoming gathering of Wake Island survivors and their wives at the house of her and her husband John. These people were at that point closer than family, bound forever by what happened on a tiny atoll in the middle of a vast ocean.

The article below is what I wrote at the time, but there are two caveats: First, I apparently misspelled some names. I’ve corrected this at the bottom of this post with their bios. And second, this represents nowhere near everything I was told that day. I felt like an eavesdropper, someone who could watch and hear them, but who was so far removed from their time and experience that comprehension was impossible.

In 2016, the daughter of Tony Schawang of Falls City, NE, the man into whose soybeans Braniff 250 fell in 1966, told me an anecdote about her father, who landed on Omaha Beach 75 years ago. She said she once asked him about that day and he said, “Girlie, you don’t need to know anything about that kind of thing.” He was right.

A photographer took Tony’s picture the morning after the Braniff crash. He looks shell-shocked. I could only imagine the horror of seeing 42 dead people and a crashed airliner fall to earth in front of you. But after finding out that Tony had already seen way worse in 1944 made that picture clearer, more understandable. That’s a thousand-yard stare he has in that 1966 photo. I will now always wonder if he was seeing the wreckage of Braniff 250 … or the wreckage of Omaha Beach. Or a bloody mashing together of both. (As much as I respect Mr. Schawang, as the photos above attest, I disagree. We should always know, and see, the consequences of war.)

Now that we’re older, we can understand, and value, more of the meaning and reality of all this, but those Marines and their wives (and Tony Schawang) are now gone. We can’t have conversations with them just because we’re older and wiser and can now listen to them. They’re lost to history … and we’re much the poorer for it.

What do I now know? Don’t put D-Day in service to American (or British) exceptionalism or nationalism or patriotism, and don’t “thank” a veteran for his/her “service.” Man up, grow up and face up to the reality that no one wanted to “serve” us on the cold Normandy sand. They wanted to simply survive. The hard truth is that D-Day (and Wake Island) represented a failure. A failure to confront, contain and eliminate human anger, violence, and hatred in service to nationalistic ideologies in Japan, Germany and Italy. The failure to do that consumed, between 1914 and 1945 upwards of 150 million lives around the world. WWII soldiers HAD to “serve” at Omaha Beach because WE failed to protect THEM.

Instead of “Thank you for your service,” try, “We’re sorry you had to expend your blood, sweat, tears and toil to clean up our monumental failings.” Every time you meet one of the dwindling numbers of WWII veterans (and those of all the other magnificent little American wars we’ve fallen into), keep your mouth shut and your brain focused on peace. These “Greatest Generation” folks answered the bell and won the fight. We might not be as blessed next time.

Here are the original two Wake Island articles:

Memory Of WWII Still Vivid For Vets

(Part I of the Wake Island Story)

‘Considering the power accumulated for the invastion of Wake Island and the meager forces of the defenders, it was one of the most humiliating defeats the Japanese Navy ever suffered.’

—Masatake Okumiya, commander, Japanese Imperial Navy

By Steve Pollock

The Duncan (OK) Banner)

Sunday, August 13, 1989

MARLOW – It all came back to them this weekend – the stark terror of facing death while kneeling naked on a sandy beach the stinking hold of the prison ship; the brutality of the Japanese; the obliteration of youthful innocence.

They fought and bled for a two-and-a-half-square-mile horseshoe of an atoll in the midPacific called Wake Island. They were United States Marines and they did their duty.

There were 10 [sic] men of that Wake Island garrison at the Marlow home of John Smith this weekend. With Smith, they talked, drank and smoked their way through the weekend, laughter masking deeper emotions of brotherhood, camaraderie and painful memories.

In the Smith kitchen, their wives continued the latest of an ongoing series of therapy sessions, attempting to exorcise some of the demons of the last 44 years of their lives with the hometown heroes.

In 1941, with war inevitable, the U.S. government began construction of a series of defensive Pacific Ocean outposts, including Wake, designed to protect against Japanese aggression. They were a little late.

Little Wake atoll, with some 1,616 Marines and civilians huddled on its three islands, was attacked at noon, Dec. 8, 1941, several hours after Pearl Harbor.

The Marines knew war was possible, but “didn’t think the little brown guys had the guts to hit us,” one of them said.

Jess Nowlin’s hearing aid battery is getting a little weak as the afternoon wears on, but his memory and sense of humor are still sharp.

He said the Marines were going about their business when they heard the drone of approaching aircraft.

“We thought they were B- 17’s out of Pearl coming in to refuel. They weren’t. They broke out of a cloud bank at about 1,800 feet, bomb bay doors open. They tore us up,” Nowlin said.

The Japanese attacked from sea and air, but the Marines held out until Dec. 23; only 400 remained to defend 21 miles of shoreline from 25 warships and a fleet of aircraft. Surrender was inevitable.

Through a haze of cigarette smoke, Robert Mac Brown, a veteran not only of World War II, but of Korea and three tours of duty in Vietnam, remembers the post-surrender scene on the beach.

“We were stripped naked and they hog-tied us with our own telephone wire. A squall came through, but lasted only about 10 to 15 minutes. One of my clearest memories of the whole operation is of watching the water run down the bare back of the guy in front of me,” Brown said.

Japanese soldiers lay on the sand in front of the prisoners, swinging machine guns back and forth. The click of rounds being loaded into chambers was ominous. Fingers tightened on triggers.

“There was an argument between the landing force commander and a guy with the fleet. They screamed at each other in Japanese, arguing about whether to kill us or not,” Brown said.

The Marines made their peace and prepared to die.

The argument to make prisoners of the Marines and civilians won the day. The prisoners were allowed to grab what clothing they could to cover themselves.

And then a living hell began which would only be ended by the birth of atomic stars over southern Japan nearly four years later.

Taken off the island on small ships, the prisoners were forced to climb up the side of the Nittamaru, a former cruise ship pitching about on rough seas.

As the men walked back through the ship and down to the hold, the crew beat them with bamboo sticks, in a gauntlet of brutality.

Packed in the stinking hold, several hundred Marines and civilians had only one five-gallon bucket per deck to hold human waste. For the 14 days of the Nittamaru’s passage from Wake to Shanghai, they could barely move.

The cold of Shanghai was felt through their thin tropical khaki. It was January 1942. Robert Brown was to have married his girl on January 12. She married someone else.

“I thought you were dead,” she later told him.

From Shanghai, through Nanking, Peking, Manchuria and Pusan, Korea, the group journeyed in packed cattle cars to their eventual destination, a coal mine on the Japanese island of Hokkaido, where they dug in the shafts alongside third-generation Korean slave labor.

They were slaves themselves until August 1945.

“Thank God for Harry S. Truman and the atomic bomb,” several survivors said, as the others echoed that prayer.

They went home to heroes’ welcomes, but the public ”’never fully appreciated or understood what we did,” Nowlin said.

They’re much older now — in their 60’s and 70’s — and it was a family reunion of sorts; they claim to be closer than brothers. They don’t miss their “get-togethers” for anything in the world; Robert Haidinger traveled from San Diego with a long chest incision after recently undergoing a major operation.

As they gazed through the Oklahoma sunshine, they didn’t see the cow bam beyond the lovegrass rippling in the August breeze; it was a Japanese destroyer was steaming close in to end their lives all over again.

“It was awful, terrible; I wouldn’t have missed it for anything; you couldn’t get me to do it again for a billion dollars,” Nowlin summed it up.

The men: Tony Obre [sic], Fallbrook, Calif; Robert Haidinger, San Diego, Calif.; Robert Murphy, Thermopolis, Wyo.; Dale Milburn [sic], Santa Rosa, Calif.; George McDaniels [sic], Dallas, Texas; Jess Nowlin, Bonham, Texas; Jack Cook, Golden, Colo.; Robert Mac Brown, Phoenix, Ariz.; Jack Williamson, Lawton; Paul Cooper, Marlow, and John Smith, Marlow.

The cost of the defense of Wake Island, from Dec. 8 to 23, 1941: Americans: 46 Marines, 47 civilians, three sailors and 11 airplanes; Japanese: 5,700 men, 11 ships and 29 airplanes.

Wives Cope With Husband’s Memories

(Part II of the Wake Island Story)

By Steve Pollock

The Duncan (OK) Banner

Sunday, August 13, 1989

MARLOW – It all came back to them this weekend – fists lashing out during nightmares, the traumatic memories, the attempts to catch up on lost time.

The wives of 10 Wake Island survivors met in Marlow with their husbands this weekend for reasons of their own.

“We go through therapy every time we get together. We help each other with problems,” they said.

The wives: Florence Haidinger, Maxine Murphy, Opal Milburn [sic], Irene McDaniels [sic], Sarah Nowlin, Betty Cook, Millie Brown, Jo Williamson, Juanita Cooper and Marie Smith.

They did their own bit during World War II: The Red Cross, an airplane factory in Detroit, North American Aviation in El Segundo, Calif, Douglas in Los Angeles, the Kress dime store.

They married their men after the long national nightmare was finished, and their lives became entwined by one event: the Japanese attack on Wake Island Dec. 8-23,1941.

Since the first reunion of Wake survivors and their spouses in 1953, these women have been like sisters.

“We love each other, we’re closer than family,” Jo Williamson said.

In Marie Smith’s kitchen, therapy was doled out in a catharsis of talk little different from that of the men gathered on the patio. Talk is said to be good for the soul; these women heal great tears in theirs every time they see each other.

According to the wives, the men came home from the war, married, had children and tried to pick up where they left off.

They wanted to take care of their families and try to catch up. They were robbed of the fun times of their late teens and early 20’s, the women unanimously agree.

“They have also lived every day as if it were their last,” Sarah Nowlin said.

The men needed some help after their harrowing battle and brutal three -and-a-half-year captivity.

According to the women, doctors never realized therapy was in order: “They never got anything.”

One man lashed out with his fists during nightmares; after a few pops, his wife learned to leave the room. Another would slide out of bed and assume a rigid posture on the floor, arms and legs folded. Yet they have all been gentle men.

“I’ve never seen my husband harm or even verbally abuse anyone,” a wife said Reunions such as this help the men and women deal with life as they age. The youths of 16-22 are now grandfathers and grandmothers in their 60’s and 70’s.

Life today is a bit baffling to them.

Extremely proud of their men, the women have no patience with draft dodgers, flag burners, Japanese cars or foreign ownership of America.

They didn’t agree with the Vietnam war policy, but duty to country should have come first, they said.

“I didn’t want my son to go to Vietnam, but I would have been ashamed of him if he hadn’t,” one said.

The issue of flag burning stirs violent protest and emotion in the group: “Made in America”’ labels are on everything they buy.

And the younger generation does not enjoy the women’s confidence: “I don’t think they could do what we were all called on to do,” they agreed.

And as Marlow afternoon shadows grew longer, the women of Wake continued to cleanse their souls.

Updated bios (confirmed via findagrave.com):

• Cpl. Robert Mac Brown, USMC, Phoenix, AZ.

Birth: 1-Feb-1918.

Death: 21-Sep-2002 (age 84).

Buried: Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, VA.

• Sgt. Jack Beasom Cook, USMC, Golden, CO.

Birth: 18-Jun-1918, Okmulgee, OK.

Death: 20-Nov-1999 (age 81).

Buried: Fort Logan National Cemetery, Denver, CO.

• Sgt. Paul Carlton Cooper, USMC, Marlow, OK.

Birth: 30-Oct-1918, Richardson, TX.

Death: 18-Sep-1994 (age 75), Marlow, OK.

Buried: Marlow Cemetery, Marlow, OK.

• Cpl. Robert Fernand Haidinger, USMC, San Diego, CA.

Birth: 24-Nov-1918, Chicago, IL.

Death: 7-Mar-2014 (age 95).

Buried: Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery, San Diego, CA.

• PFC Robert Bruce “Bob” Murphy, USMC, Thermopolis, WY.

Birth: 5-Oct-1920, Thermopolis, WY.

Death: 5-Feb-2007 (age 86), Hot Springs County, WY.

Buried: Monument Hill Cemetery, Thermopolis, WY.

• Pvt. Ival Dale Milbourn, USMC, Phoenix, AZ.

Birth: 23-Jul-1922, Saint Joseph, MO.

Death: 18-Dec-2001 (age 79), Mesa, AZ.

Buried: Skylawn Memorial Park, San Mateo, CA.

• PFC George Washington “Dub” McDaniel, Dallas, TX.

Birth: 23-Dec-1915, Stigler, OK.

Death: 14-Jul-1993 (age 77).

Buried: Stigler Cemetery, Stigler, OK.

• PFC Jesse Elmer Nowlin, USMC, Bonham, TX.

Birth: 9-Dec-1915, Leonard, TX.

Death: 13-Sep-1990 (age 74), Bonham, TX.

Buried: Willow Wild Cemetery, Bonham, TX.

• MSgt. Tony Theodule Oubre, USMC (ret.), Fallbrook, CA.

Birth: 17-Aug-1919, Loreauville, Iberia Parish, LA.

Death: 7-Feb-2005 (age 85).

Buried: Riverside National Cemetery, Riverside, CA.

• Pvt. John Clarence Smith, Marlow, OK.

Birth: 11-Mar-1918.

Death: 19-Jan-1994 (age 75).

Buried: Marlow Cemetery, Marlow, OK.

• Sgt. Jack Russell “Rusty” Williamson, Jr., USMC, Lawton, OK.

Birth: 26-Jul-1919, Lawton, OK.

Death: 12-Jul-1996 (age 76).

Buried: Highland Cemetery, Lawton, OK.

The wives (I couldn’t confirm the details for all of them):

• Juanita Belle Sehested Cooper

Birth: 5-Dec-1920, Marlow, OK.

Death: 28-Jul-2001 (age 80), Beaverton, OR.

Buried: Marlow Cemetery, Marlow, OK.

• Florence A Haidinger

Birth: 31-Dec-1934.

Death: 26-Sep-2014 (age 79).

Buried: Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery, San Diego, CA.

• Irene McDaniel

Birth: 24-Nov-1918.

Death: 7-Mar-2004 (age 85).

Buried: Stigler Cemetery, Stigler, OK.

• Maxine Gertrude Gwynn Murphy

Birth: 10-Nov-1923.

Death: 4-Mar-1996 (age 72).

Buried: Monument Hill Cemetery, Thermopolis, WY.

• Marie A. Smith

Birth: 11-Feb-1929.

Death: 16-Nov-1997 (age 68).

Buried: Marlow Cemetery, Marlow, OK.

• Emily Jo Lane Williamson

Birth: 30-Mar-1924, Texas.

Death: 3-Jun-2007 (age 83), Comanche County, OK.

Buried: Sunset Memorial Gardens, Lawton, OK.

«One of the most brilliant things I’ve seen in a long time». Steve Bell and The Guardian continue to hit these out of the park. Go there and read, donate, support. They cover the U.S. as, if not more, effectively than the Times and Post or any other American news organization. Not that those exist anymore, but still.

Far more importantly, RIP Kurds. From you stretching back all the way to Columbus is a long, unbroken trail of genocide. Perhaps things will be just a tiny, marginally bit better in 2021. Knowing other Americans as I do, I’m not holding my breath. I am sincerely sorry that you will not have breath to hold until 2021. What a treasonous betrayal.

Impeach. Remove.

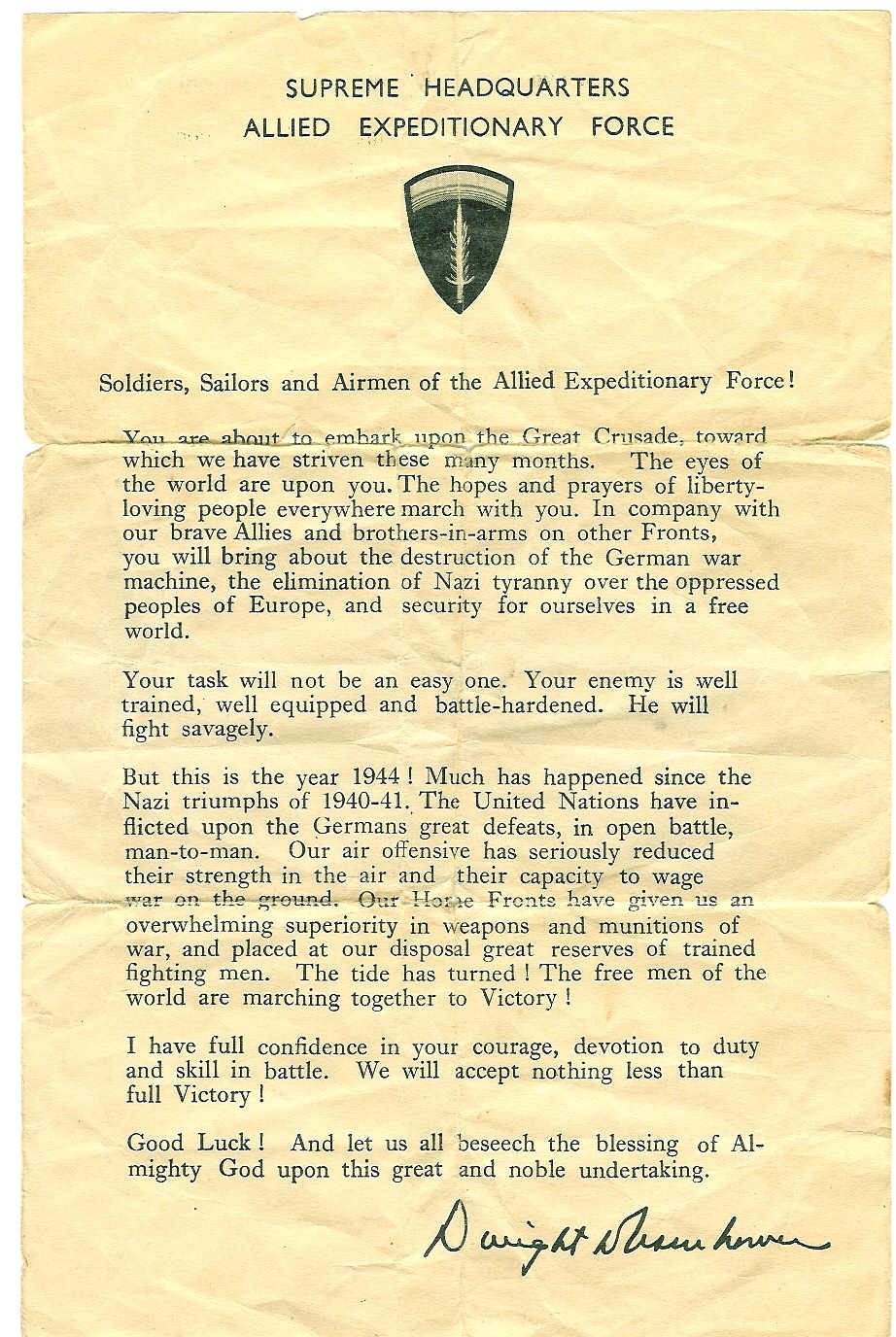

As they moved off the beaches after 6-Jun-44, U.S. service personnel read this. Here are some particularly important excerpts.

Pocket Guide to France

Prepared by Army Information Branch, Army Services Forces, Information and Education Division, United States Army

War and Navy Departments, Washington, D.C.

1944

“Why You’re Going to France

“You are about to play a personal part in pushing the Germans out of France. Whatever part you take—rifleman, hospital orderly, mechanic, pilot, clerk, gunner, truck driver—you will be an essential factor in a great effort which will have two results: first, France will be liberated from the Nazi mob and the Allied armies will be that much nearer Virtory, and second, the enemy will be deprived of coal, steel, manpower, machinery, food, bases, seacoast and a long list of other essentials which have enabled him to carry on the war at the expense of the French.

“The Allied offensive you are taking part in is based upon a hard-boiled fact. It’s this. We democracies aren’t just doing favors in fighting for each other when history gets tough. We’re all in the same boat. Take a look around you as you move into France and you’ll see what the Nazis to to a democracy when they can get it down by itself.”

…

“A Few Pages of French History

“Not only French ideas but French guns helped us to become a nation. Don’t forget that liberty loving Lafayette and his friends risked their lives and fortunes to come to the aid of General George Washington at a moment in our opening history when nearly all the world was against us. In the War for Independence which our ragged army was fighting, every man and each bullet counted. Frenchmen gave us their arms and their blood when they counted most. Some 45,000 Frenchmen crossed the Atlantic to help us. They came in cramped little ships of two or three hundred tons requiring two months or more for the crossing. We had no military engineers; French engineers designed and built our fortifications. We had little money; the French lent us over six million dollars and gave us over three million more.

“In the same fighting spirit we acted as France’s alliy in 1917 and 1918 when our A.E.F. went into action. In that war, France, which is about a fourteenth of our size, lost nearly eighteen times more men than we did, fought twice as long and had an eighth of her country devastated.”

…

“In Parting

Pocket Guide to France, US Army

“We are friends of the French and they are friends of ours.

“The Germans are our enemies and we are theirs.

“Some of the secret agents who have been spying on the French will no doubt remain to spy on you. Keep a close mouth. No bragging about anything.

‘No belittling either. Be generous; it won’t hurt.

“Eat what is given you in your own unit. Don’t go foraging among the French. They can’t afford it.

‘Boil all drinking water unless it has been approved by a Medical Officer.

‘You are a member of the best dressed, best fed, best equipped liberating Army now on earth. You are going in among the people of a former Ally of your country. They are still your kind of people who happen to speak democracy in a different language. Americans among Frenchmen, let us remember our likenesses, not our differences. The Nazi slogan for destroying us both was “Divide and Conquer.” Our American answer is “In Union There Is Strength.””

“No bragging or belittling.” “Remember our likenesses, not our differences.” “In Union There is Strength.”

How refreshing.

[Yes, the pics are graphic. Look at them. Own them. Be glad they’re in black and white.]

As the 75th anniversary of the launch of Overlord arrives, it’s important to remember that it was just part of a very big picture, the beginning of the end of World War II. Up until that point, it had been a very long, very hard slog. But afterwards you could practically see directly from the beaches of Utah, Omaha, Sword, Juno and Gold on 6-Jun-1944 to the deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on 2-Sep-1945. The war now had its expiration date.

No one cheered harder for the faint glimpse of the end than P.o.W.s in Japan, Korea and China. A few of those had survived four years of torture, starvation, beatings, illnesses such as beri-beri and even being bombarded by their own Army Air Force; they were the survivors of Wake Island, which resisted overwhelming Japanese invasion forces between 8-Dec and 23-Dec-1941. Had it not been for Overlord and Manhattan, those men would have died. Instead, they beat the odds thanks to Truman and Ike, Normandy and Trinity. (To quote directly: “Thank God for Harry Truman and thank God for the atom bomb!”)

I always think back to 1989, when as a newspaper reporter, I was privileged to meet just 11 of the Wake Island survivors, who gathered fairly often for small-scale reunions. That year, while working as a reporter who occasionally wrote some features about WWII vets, I got a call from a friend of mine, Marie Smith, (who had kept me sane during my cursed four months while we worked at <shudder> Wal-Mart), to tell me about an upcoming gathering of Wake Island survivors and their wives at the house of her and her husband John. These people were at that point closer than family, bound forever by what happened on a tiny atoll in the middle of a vast ocean.

The article below is what I wrote at the time, but there are two caveats: First, I apparently misspelled some names. I’ve corrected this at the bottom of this post with their bios. And second, this represents nowhere near everything I was told that day. I felt like an eavesdropper, someone who could watch and hear them, but who was so far removed from their time and experience that comprehension was impossible.

In 2016, the daughter of Tony Schawang of Falls City, NE, the man into whose soybeans Braniff 250 fell in 1966, told me an anecdote about her father, who landed on Omaha Beach 75 years ago. She said she once asked him about that day and he said, “Girlie, you don’t need to know anything about that kind of thing.” He was right.

A photographer took Tony’s picture the morning after the Braniff crash. He looks shell-shocked. I could only imagine the horror of seeing 42 dead people and a crashed airliner fall to earth in front of you. But after finding out that Tony had already seen way worse in 1944 made that picture clearer, more understandable. That’s a thousand-yard stare he has in that 1966 photo. I will now always wonder if he was seeing the wreckage of Braniff 250 … or the wreckage of Omaha Beach. Or a bloody mashing together of both. (As much as I respect Mr. Schawang, as the photos above attest, I disagree. We should always know, and see, the consequences of war.)

Now that we’re older, we can understand, and value, more of the meaning and reality of all this, but those Marines and their wives (and Tony Schawang) are now gone. We can’t have conversations with them just because we’re older and wiser and can now listen to them. They’re lost to history … and we’re much the poorer for it.

What do I now know? Don’t put D-Day in service to American (or British) exceptionalism or nationalism or patriotism, and don’t “thank” a veteran for his/her “service.” Man up, grow up and face up to the reality that no one wanted to “serve” us on the cold Normandy sand. They wanted to simply survive. The hard truth is that D-Day (and Wake Island) represented a failure. A failure to confront, contain and eliminate human anger, violence, and hatred in service to nationalistic ideologies in Japan, Germany and Italy. The failure to do that consumed, between 1914 and 1945 upwards of 150 million lives around the world. WWII soldiers HAD to “serve” at Omaha Beach because WE failed to protect THEM.

Instead of “Thank you for your service,” try, “We’re sorry you had to expend your blood, sweat, tears and toil to clean up our monumental failings.” Every time you meet one of the dwindling numbers of WWII veterans (and those of all the other magnificent little American wars we’ve fallen into), keep your mouth shut and your brain focused on peace. These “Greatest Generation” folks answered the bell and won the fight. We might not be as blessed next time.

Here are the original two Wake Island articles:

Memory Of WWII Still Vivid For Vets

(Part I of the Wake Island Story)

‘Considering the power accumulated for the invastion of Wake Island and the meager forces of the defenders, it was one of the most humiliating defeats the Japanese Navy ever suffered.’

—Masatake Okumiya, commander, Japanese Imperial Navy

By Steve Pollock

The Duncan (OK) Banner)

Sunday, August 13, 1989

MARLOW – It all came back to them this weekend – the stark terror of facing death while kneeling naked on a sandy beach the stinking hold of the prison ship; the brutality of the Japanese; the obliteration of youthful innocence.

They fought and bled for a two-and-a-half-square-mile horseshoe of an atoll in the midPacific called Wake Island. They were United States Marines and they did their duty.

There were 10 [sic] men of that Wake Island garrison at the Marlow home of John Smith this weekend. With Smith, they talked, drank and smoked their way through the weekend, laughter masking deeper emotions of brotherhood, camaraderie and painful memories.

In the Smith kitchen, their wives continued the latest of an ongoing series of therapy sessions, attempting to exorcise some of the demons of the last 44 years of their lives with the hometown heroes.

In 1941, with war inevitable, the U.S. government began construction of a series of defensive Pacific Ocean outposts, including Wake, designed to protect against Japanese aggression. They were a little late.

Little Wake atoll, with some 1,616 Marines and civilians huddled on its three islands, was attacked at noon, Dec. 8, 1941, several hours after Pearl Harbor.

The Marines knew war was possible, but “didn’t think the little brown guys had the guts to hit us,” one of them said.

Jess Nowlin’s hearing aid battery is getting a little weak as the afternoon wears on, but his memory and sense of humor are still sharp.

He said the Marines were going about their business when they heard the drone of approaching aircraft.

“We thought they were B- 17’s out of Pearl coming in to refuel. They weren’t. They broke out of a cloud bank at about 1,800 feet, bomb bay doors open. They tore us up,” Nowlin said.

The Japanese attacked from sea and air, but the Marines held out until Dec. 23; only 400 remained to defend 21 miles of shoreline from 25 warships and a fleet of aircraft. Surrender was inevitable.

Through a haze of cigarette smoke, Robert Mac Brown, a veteran not only of World War II, but of Korea and three tours of duty in Vietnam, remembers the post-surrender scene on the beach.

“We were stripped naked and they hog-tied us with our own telephone wire. A squall came through, but lasted only about 10 to 15 minutes. One of my clearest memories of the whole operation is of watching the water run down the bare back of the guy in front of me,” Brown said.

Japanese soldiers lay on the sand in front of the prisoners, swinging machine guns back and forth. The click of rounds being loaded into chambers was ominous. Fingers tightened on triggers.

“There was an argument between the landing force commander and a guy with the fleet. They screamed at each other in Japanese, arguing about whether to kill us or not,” Brown said.

The Marines made their peace and prepared to die.

The argument to make prisoners of the Marines and civilians won the day. The prisoners were allowed to grab what clothing they could to cover themselves.

And then a living hell began which would only be ended by the birth of atomic stars over southern Japan nearly four years later.

Taken off the island on small ships, the prisoners were forced to climb up the side of the Nittamaru, a former cruise ship pitching about on rough seas.

As the men walked back through the ship and down to the hold, the crew beat them with bamboo sticks, in a gauntlet of brutality.

Packed in the stinking hold, several hundred Marines and civilians had only one five-gallon bucket per deck to hold human waste. For the 14 days of the Nittamaru’s passage from Wake to Shanghai, they could barely move.

The cold of Shanghai was felt through their thin tropical khaki. It was January 1942. Robert Brown was to have married his girl on January 12. She married someone else.

“I thought you were dead,” she later told him.

From Shanghai, through Nanking, Peking, Manchuria and Pusan, Korea, the group journeyed in packed cattle cars to their eventual destination, a coal mine on the Japanese island of Hokkaido, where they dug in the shafts alongside third-generation Korean slave labor.

They were slaves themselves until August 1945.

“Thank God for Harry S. Truman and the atomic bomb,” several survivors said, as the others echoed that prayer.

They went home to heroes’ welcomes, but the public ”’never fully appreciated or understood what we did,” Nowlin said.

They’re much older now — in their 60’s and 70’s — and it was a family reunion of sorts; they claim to be closer than brothers. They don’t miss their “get-togethers” for anything in the world; Robert Haidinger traveled from San Diego with a long chest incision after recently undergoing a major operation.

As they gazed through the Oklahoma sunshine, they didn’t see the cow bam beyond the lovegrass rippling in the August breeze; it was a Japanese destroyer was steaming close in to end their lives all over again.

“It was awful, terrible; I wouldn’t have missed it for anything; you couldn’t get me to do it again for a billion dollars,” Nowlin summed it up.

The men: Tony Obre [sic], Fallbrook, Calif; Robert Haidinger, San Diego, Calif.; Robert Murphy, Thermopolis, Wyo.; Dale Milburn [sic], Santa Rosa, Calif.; George McDaniels [sic], Dallas, Texas; Jess Nowlin, Bonham, Texas; Jack Cook, Golden, Colo.; Robert Mac Brown, Phoenix, Ariz.; Jack Williamson, Lawton; Paul Cooper, Marlow, and John Smith, Marlow.

The cost of the defense of Wake Island, from Dec. 8 to 23, 1941: Americans: 46 Marines, 47 civilians, three sailors and 11 airplanes; Japanese: 5,700 men, 11 ships and 29 airplanes.

Wives Cope With Husband’s Memories

(Part II of the Wake Island Story)

By Steve Pollock

The Duncan (OK) Banner

Sunday, August 13, 1989

MARLOW – It all came back to them this weekend – fists lashing out during nightmares, the traumatic memories, the attempts to catch up on lost time.

The wives of 10 Wake Island survivors met in Marlow with their husbands this weekend for reasons of their own.

“We go through therapy every time we get together. We help each other with problems,” they said.

The wives: Florence Haidinger, Maxine Murphy, Opal Milburn [sic], Irene McDaniels [sic], Sarah Nowlin, Betty Cook, Millie Brown, Jo Williamson, Juanita Cooper and Marie Smith.

They did their own bit during World War II: The Red Cross, an airplane factory in Detroit, North American Aviation in El Segundo, Calif, Douglas in Los Angeles, the Kress dime store.

They married their men after the long national nightmare was finished, and their lives became entwined by one event: the Japanese attack on Wake Island Dec. 8-23,1941.

Since the first reunion of Wake survivors and their spouses in 1953, these women have been like sisters.

“We love each other, we’re closer than family,” Jo Williamson said.

In Marie Smith’s kitchen, therapy was doled out in a catharsis of talk little different from that of the men gathered on the patio. Talk is said to be good for the soul; these women heal great tears in theirs every time they see each other.

According to the wives, the men came home from the war, married, had children and tried to pick up where they left off.

They wanted to take care of their families and try to catch up. They were robbed of the fun times of their late teens and early 20’s, the women unanimously agree.

“They have also lived every day as if it were their last,” Sarah Nowlin said.

The men needed some help after their harrowing battle and brutal three -and-a-half-year captivity.

According to the women, doctors never realized therapy was in order: “They never got anything.”

One man lashed out with his fists during nightmares; after a few pops, his wife learned to leave the room. Another would slide out of bed and assume a rigid posture on the floor, arms and legs folded. Yet they have all been gentle men.

“I’ve never seen my husband harm or even verbally abuse anyone,” a wife said Reunions such as this help the men and women deal with life as they age. The youths of 16-22 are now grandfathers and grandmothers in their 60’s and 70’s.

Life today is a bit baffling to them.

Extremely proud of their men, the women have no patience with draft dodgers, flag burners, Japanese cars or foreign ownership of America.

They didn’t agree with the Vietnam war policy, but duty to country should have come first, they said.

“I didn’t want my son to go to Vietnam, but I would have been ashamed of him if he hadn’t,” one said.

The issue of flag burning stirs violent protest and emotion in the group: “Made in America”’ labels are on everything they buy.

And the younger generation does not enjoy the women’s confidence: “I don’t think they could do what we were all called on to do,” they agreed.

And as Marlow afternoon shadows grew longer, the women of Wake continued to cleanse their souls.

Updated bios (confirmed via findagrave.com):

• Cpl. Robert Mac Brown, USMC, Phoenix, AZ.

Birth: 1-Feb-1918.

Death: 21-Sep-2002 (age 84).

Buried: Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, VA.

• Sgt. Jack Beasom Cook, USMC, Golden, CO.

Birth: 18-Jun-1918, Okmulgee, OK.

Death: 20-Nov-1999 (age 81).

Buried: Fort Logan National Cemetery, Denver, CO.

• Sgt. Paul Carlton Cooper, USMC, Marlow, OK.

Birth: 30-Oct-1918, Richardson, TX.

Death: 18-Sep-1994 (age 75), Marlow, OK.

Buried: Marlow Cemetery, Marlow, OK.

• Cpl. Robert Fernand Haidinger, USMC, San Diego, CA.

Birth: 24-Nov-1918, Chicago, IL.

Death: 7-Mar-2014 (age 95).

Buried: Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery, San Diego, CA.

• PFC Robert Bruce “Bob” Murphy, USMC, Thermopolis, WY.

Birth: 5-Oct-1920, Thermopolis, WY.

Death: 5-Feb-2007 (age 86), Hot Springs County, WY.

Buried: Monument Hill Cemetery, Thermopolis, WY.

• Pvt. Ival Dale Milbourn, USMC, Phoenix, AZ.

Birth: 23-Jul-1922, Saint Joseph, MO.

Death: 18-Dec-2001 (age 79), Mesa, AZ.

Buried: Skylawn Memorial Park, San Mateo, CA.

• PFC George Washington “Dub” McDaniel, Dallas, TX.

Birth: 23-Dec-1915, Stigler, OK.

Death: 14-Jul-1993 (age 77).

Buried: Stigler Cemetery, Stigler, OK.

• PFC Jesse Elmer Nowlin, USMC, Bonham, TX.

Birth: 9-Dec-1915, Leonard, TX.

Death: 13-Sep-1990 (age 74), Bonham, TX.

Buried: Willow Wild Cemetery, Bonham, TX.

• MSgt. Tony Theodule Oubre, USMC (ret.), Fallbrook, CA.

Birth: 17-Aug-1919, Loreauville, Iberia Parish, LA.

Death: 7-Feb-2005 (age 85).

Buried: Riverside National Cemetery, Riverside, CA.

• Pvt. John Clarence Smith, Marlow, OK.

Birth: 11-Mar-1918.

Death: 19-Jan-1994 (age 75).

Buried: Marlow Cemetery, Marlow, OK.

• Sgt. Jack Russell “Rusty” Williamson, Jr., USMC, Lawton, OK.

Birth: 26-Jul-1919, Lawton, OK.

Death: 12-Jul-1996 (age 76).

Buried: Highland Cemetery, Lawton, OK.

The wives (I couldn’t confirm the details for all of them):

• Juanita Belle Sehested Cooper

Birth: 5-Dec-1920, Marlow, OK.

Death: 28-Jul-2001 (age 80), Beaverton, OR.

Buried: Marlow Cemetery, Marlow, OK.

• Florence A Haidinger

Birth: 31-Dec-1934.

Death: 26-Sep-2014 (age 79).

Buried: Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery, San Diego, CA.

• Irene McDaniel

Birth: 24-Nov-1918.

Death: 7-Mar-2004 (age 85).

Buried: Stigler Cemetery, Stigler, OK.

• Maxine Gertrude Gwynn Murphy

Birth: 10-Nov-1923.

Death: 4-Mar-1996 (age 72).

Buried: Monument Hill Cemetery, Thermopolis, WY.

• Marie A. Smith

Birth: 11-Feb-1929.

Death: 16-Nov-1997 (age 68).

Buried: Marlow Cemetery, Marlow, OK.

• Emily Jo Lane Williamson

Birth: 30-Mar-1924, Texas.

Death: 3-Jun-2007 (age 83), Comanche County, OK.

Buried: Sunset Memorial Gardens, Lawton, OK.

Is corporate power absolute yet? Or just overwhelming? Maybe … it’s just … mestastizing? There’s a fascinating documentary over at Deutsche Welle:

“The Wallonia region in Belgium triggered a Europe-wide crisis in the fall of 2016 by refusing to sign the CETA free trade agreement with Canada, as millions of EU citizens took to the streets to protest against the agreement. The CETA negotiations had turned the spotlight on the system of private arbitration courts. … Many states whose sovereignty is threatened are now finally waking up to the danger. But is it perhaps already too late to do anything about the seemingly over-mighty corporations?”

Deutsche Welle

Immoral, indecent, inhumane. There is no slippery slope; this country is on a well-trodden path dating back at least to 1492. There is also no false equivalency. We are running concentration camps and human beings are dying. [Full Stop]

Details are in the OIG report to DHS. Full report is here.

And then Primo Levi pegged the inevitable results of such greed, hypocrisy, selfishness … and our addiction to those three destructive forces:

“Auschwitz is outside of us, but it is all around us, in the air. The plague has died away, but the infection still lingers and it would be foolish to deny it. Rejection of human solidarity, obtuse and cynical indifference to the suffering of others, abdication of the intellect and of moral sense to the principle of authority, and above all, at the root of everything, a sweeping tide of cowardice, a colossal cowardice which masks itself as warring virtue, love of country and faith in an idea.”

Primo Levi

And the college students of the White Rose in Munich, 1942, in a pamphlet that would lead to their executions, also outlined how it’s impossible to have rational, intellectual discourse with those who have devoted themselves to irrational, anti-intellectual rot:

“It is impossible to engage in intellectual discourse with National Socialist Philosophy. For if there were such an entity, one would have to try by means of analysis and discussion either to prove its validity or to combat it. In actuality we face a [different] situation. At its very inception this movement depended on the deception and betrayal of one’s fellow man.”

The White Rose Society, 1942

No. You cannot argue with Fascists or Nazis or ignorant nationalists. Rational arguments won’t win over irrational people.

A preface: I became interested in World War One history about 40 years ago, reading Elleston Trevor’s “Bury Him Among Kings,” a novel (undoubtedly my

But it’s never really packed a personal punch. While many in our extended families fought in the Civil War, most were too young or too old for the world wars. One exception was our Uncle Louie Webb, who served in World War Two (and how I wish I could ask him about it!) and our Grandpa Pollock’s oldest brother Mearon Edgar, who was born in 1894 and is our father’s namesake. Edgar (as Dad called him) was a World War One veteran and he placed a small ad in the American Legion Magazine of August, 1937: “800th Aero Repair Squadron—Proposed reunion, Los Angeles, Calif., late summer or fall. Mearon E. Pollock, 306 N. Maple dr., Beverly Hills, Calif.” He was apparently the principal organizer of such squadron reunions up until World War Two. After the first war, he and his wife moved to Beverly Hills from Oklahoma. He was a barber with a shop on Wilshire Boulevard; she was a Beverly Hills public school teacher. They later farmed in Oregon and California, where he died around 1977. Interesting stuff, albeit a bit dry. The history of war should never be dry and dusty and divorced from our emotions. It should be as war itself: visceral, devastating, obscene to sight, offensive to smell, deafening to hearing. Hence the following post.

100 years ago today, at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, the guns along the 440-mile line stretching from Switzerland to the North Sea fell silent. The war started 1 August 1914 just as German Chancellor Otto von Bismark once famously predicted around 1884, by “some damned fool thing in the Balkans;” in this case, the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, a city of agony in the 20th century). But on 11 November 1918, it was finally “all quiet on the Western Front.”

We remember all this today because as Polish poet Czesław Miłosz wrote, “The living owe it to those who no longer can speak to tell their story for them.”

But sometimes, the living forget those who can no longer speak and instead harness them in service of the political or the feel-good, using their severed limbs to pat ourselves on our collective backs. This rather florid inscription on the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey, London, is an example of how remembrance can often be lofty, nebulous, nameless and faceless and sanitized and ultimately divorced from the nightmare reality of the war and how it was experienced by the men and women caught in it:

“Beneath this stone rests the body of a British warrior, unknown by name or rank, brought from France to lie among the most illustrious of the land and buried here on Armistice Day, 11 Nov: 1920, in the presence of His Majesty King George V, his Ministers of State, the Chiefs of his forces and a vast concourse of the nation. Thus are commemorated the many multitudes who during the Great War of 1914 – 1918 gave the most that Man can give, life itself; for God, for King and country, for loved ones, home and empire, for the sacred cause of justice and the freedom of the world. They buried him among the kings because he had done good toward God and toward his house.”

That was the official, sanitized, God-and-Country pablum version of the war. It’s fine as it goes, but the soldiers of the line saw things quite differently, and epitaphs like these tend to mute them, hide them from sight, rob them of existence.

So what’s a better way to remember then? How about starting with accounts left to us such as the prose and poetry of two British officers and a German soldier. It is their raw experiences which we should remember today, not “George V and his Ministers of State and the Chiefs of his forces” (who botched the entire affair so badly that it became an unprecedented slaughter), nor leaders gathered today at Compiegne, site of the signing of Armistice, nor the American leader shamefully cowering in his hotel in Paris, apparently afraid of rain.

Wrote British Captain Siegfried Sassoon in one of his best, sharpest, brightest harpooning poems of the “Chiefs of His Majesty’s forces”:

The General

“‘Good-morning, good-morning!’ the General said

When we met him last week on our way to the line.

Now the soldiers he smiled at are most of ’em dead,

And we’re cursing his staff for incompetent swine.

‘He’s a cheery old card,’ grunted Harry to Jack

As they slogged up to Arras with rifle and pack.“But he did for them both by his plan of attack.”

Siegfried Sassoon

British Second Lieutenant Wilfred Owen, who was killed in action just one week before the Armistice was signed, summed up his generation’s experience and wondered who would mourn them in extremely powerful poems:

Anthem for Doomed Youth

“What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

— Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells;

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs,—

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.“What candles may be held to speed them all?

Wilfrid Owen

Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.”

The German Erich Maria Remarque, in “All Quiet on the Western Front,” a book which was later burned by Hitler, added his own voice in prose:

“I am young, I am twenty years old; yet I know nothing of life but despair, death, fear, and fatuous superficiality cast over an abyss of sorrow. I see how peoples are set against one another, and in silence, unknowingly, foolishly, obediently, innocently slay one another.”

Erich Maria Remarque

…

“A man cannot realize that above such shattered bodies there are still human faces in which life goes its daily round. And this is only one hospital, a single station; there are hundreds of thousands in Germany, hundreds of thousands in France, hundreds of thousands in Russia. How senseless is everything that can ever be written, done, or thought, when such things are possible. It must be all lies and of no account when the culture of a thousand years could not prevent this stream of blood being poured out, these torture chambers in their hundreds of thousands. A hospital alone shows what war is.”

Finally, it’s worth reading what is probably Owens’ finest poem:

Dulce et Decorum Est

“Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the hauntingflares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.“Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

Andflound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.“In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.“If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Wilfrid Owen

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: ‘Dulce et decorum est

Propatria mori .'”

The old lie: “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori” roughly translates to “It is sweet and honorable to die for one’s country.” As Owen wrote, dying like cattle in warfare conducted in the cause of nationalism or patriotism is never sweet. It is an obscenity. Just see the attached photos. You should not be squeamish; stare at them and memorize them. If you vote for war, support its waging or cheer for capital punishment, you should be able to look unflinchingly at the black and white images of the consequences of bloodthirst.)

As violent forces of chauvinistic nationalism rise around us, we would do well to remember not Kings and generals, but the experience and judgement of the many Owens, Sassoons and Remarques as the central lesson of this eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 2018.

[Photo: First World War infantrymen whose faces had been mutilated in trench warfare. They were known as the “

In the next few days, there will be much remembrance of the events of 100 years ago—the end of World War I. Not as much in the U.S., where World War I is like the Korean War, a largely forgotten conflict, even though 115,516 Americans died between 1917-1918, along with over 320,000 sickened, most in the influenza epidemic of 1918.

But for Europe and the world including the U.S. in spite of our isolationism, the end of World War One is momentous, remembered, and memorialized.

From the German perspective, several 9 Novembers during the 20th century were extremely fateful; in fact, today is known in Germany as the Schicksalstag, or Day of Fate.

100 years ago today, after German sailors began to revolt against orders by the Imperial High Command to sail out for a final, climatic battle with the British Royal Navy (which the sailors considered suicidal), Chancellor Prince Max von Baden somewhat prematurely published news that Kaiser Wilhelm II had abdicated. Also prematurely, State Secretary Phlipp Scheidemann, part of the leadership of SPD, announced the formation of a new German republic: “The old and rotten, the monarchy has collapsed. The new may live. Long live the German Republic!” Events afterwards gathered speed; revolution toppled all the monarchical regimes of the German Reich, and the Germans sued for peace on the western front.

These events gave rise to a rightwing article of faith in future years: the Dolchstoßlegende, or the Stab in the Back legend, which the National Socialists would use as a foundational belief. According to the German right, the German army was still in its positions on the Western Front, undefeated, until (mainly Jewish and Socialist) politicians back in Berlin, such as Scheidemann, overthrew the Kaiser and declared the Republic, thus “stabbing in the back” the German army and navy. In spite of the fact that the Navy had mutinied and was no longer a fighting force and the German army was actually disintegrating in France and Belgium, the Dolchstoßlegende helped the German right delegitimize the Republic and prepare the way for its destruction.

An attempt at that destruction was made 95 years ago today when National Socialists and members of other nationalist parties attempted a coup in Munich. In what is now known as the Beer Hall Putsch, NSDAP leader Adolf Hitler declared himself leader in Bavaria, but the march through Munich originating in several beer halls was stopped by Bavarian police. Sixteen nationalists and four policemen were killed, the NSDAP was disbanded and Hitler was jailed. After the party’s ascent to power in 1933, 9 November was celebrated as a national holiday to remember the fallen of the putsch; any mention of the 9 November of 1918 was forbidden, unless it was a repetition of the Dolchstoßlegende.

The Dolchstoßlegende and years of similar lies and antisemitism were part of what ignited Reichskristallnacht on this day 80 years ago in 1938. Jewish synagogues and property were burned and destroyed throughout the Reich; more than 400 Jews were killed or committed suicide. About 30,000 Jews and other “undesirables” were arrested. Many later died in concentration camps. “Crystal Night” was named for the large amount of shattered glass that littered streets around the country. A final humiliation came when Jews were made responsible for the damage and those who collected on insured damages were forced to sign over insurance payments to the Reich.

And finally, on this day in 1989 29 years ago, after decades of war, destruction, the Holocaust, the Cold War and much lost territory, the Berliner Mauer (Berlin Wall) was breached and East and West Germany were reunited. Because the actual reunification occurred on the anniversary of Kristallnacht, the more formal date of 3 October 1990 is now celebrated as the official holiday.

Given that 100-150 million lives were lost around the world between roughly 1912 and 1989, 9 November is an appropriate day for a worldwide mourning.

A message in a bottle on the roof of a Goslar, Germany, cathedral was found by the grandson of the writer. An authentic lesson from history:

“On March 26, 1930, four roofers in this small west German town inscribed a message to the future. “Difficult times of war lie behind us,” they wrote. After describing the soaring inflation and unemployment that followed the First World War, they concluded, “We hope for better times soon to come.”

“The roofers rolled up the message, slid it into a clear glass bottle and hid it in the roof of the town’s 12th-century cathedral. Then they patched up the roof’s only opening.

“Eighty-eight years later, while doing maintenance work, 52-year-old roofer Peter Brandt happened upon the bottle. He recognised the letterhead of the receipt paper on which the note was written, as well as the name of one of the signatories: Willi Brandt – a shy, 18-year old roofing apprentice at the time of the note’s creation – was Peter’s grandfather.

“‘It was an exciting find,’ Peter Brandt said, given the improbability of discovering the bottle in the same roof his grandfather had repaired almost a century earlier. The letter, Brandt said, is from a dark chapter of Germany’s past. But its discovery offered an opportunity to reflect on the relative peace and prosperity of the present.

…

“Just a few years after his grandfather – who is not related to former West German chancellor Willy Brandt – signed the note, he enlisted as a soldier during World War II. He was later captured and imprisoned by the Russians. After returning to Goslar, Willi resumed his profession as a roofer but never talked about the war.”

New Zealand Herald

That the message survived the war shows that even amidst great destruction and degradation, something always survives. Humans press on, even if they have to leave their homes and try to find peace in hostile lands. Goslar’s mayor understands:

“The unemployment problems that Willi Brandt described have largely disappeared, according to Goslar Mayor Oliver Junk.

“Still, Goslar residents are moving to larger places to attend university or find work, said Ulrich Albers, head of the local archives. Stores and entire housing blocks stand empty in some parts of town.

“Three years ago, during the height of Germany’s refugee crisis, Junk made headlines when he proposed that Goslar take in additional refugees, citing the housing shortage in bigger cities. ‘It’s mad that in Göttingen they are having to build new accommodations, and are tearing their hair out as to where to put everyone, while we have empty properties and employers who are desperate for skilled workers,’ Junk told the Guardian newspaper in August 2015, referring to a nearby more populous city.

“Junk said he doesn’t regret that decision – and that the contents of Willi Brandt’s letter put it in a new perspective. ‘Every day, we’re discussing the many problems we have as a city that are allegedly very, very difficult. But with this letter from 1930, we can see that the many problems that we perceive aren’t really problems,’ he said.”

Ibid

As the line immortalized in Casablanca goes, “… it doesn’t take much to see that the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.”

Maybe not in the grand scheme of things perhaps, but I’m sure the problems Willi Brandt experienced on the Ostfront mattered to him … a great deal. And the problems he and others created on the Ostfront mattered to those they impacted even more.

Deutsche Welle reports that “a new survey published by German public broadcaster ARD shows Germans trust Russia more than the US.” Or to be specific: “28 percent of respondents felt Moscow was a reliable partner, compared to 25 percent for Washington …. More than 90 percent said Paris was a reliable partner, while more than 60 percent said Britain …”

So let’s see if I’ve got this. Germany, a country in which there are still many women alive who were raped by invading Russian Red Army soldiers and in which the human products of those rapes are still living, now trust … Russia more than the United States.

Yes, I hear you. I too am sick of all the Winning and Greatness we have achieved Again.

[Text by HawkEye. Photo by Markus Spiske via Unsplash.]